What is a witch?

Public understanding of early modern witch trials has long been shaped by myths and misconceptions – that all witches were women and that ‘witch crazes’ were caused by villainous male witch hunters.

Professor Alison Rowlands has spent decades studying witch trials in different parts of early modern Europe, unpicking what really happened and why.

Her work ensures that the names of those accused and the complex stories of why they were persecuted are never forgotten.

Estimated number of people executed for witchcraft in early modern Europe (15th - 18th century)

These numbers, collated by Wolfgang Behringer and published in Witches and Witch-Hunts. A Global History (Polity, 2004), are based on modern-day country definitions and only include those regions with over 1,000 executions. Figures are likely to have been higher.

Germany

At least 25,000 executed

France

At least 5,000 executed

Poland

At least 4,000 executed

Switzerland

At least 4,000 executed

Belgium and Luxembourg

At least 2,500 executed

Britain

At least 1,350 executed in Scotland (and at least 500 executed in England, not recorded by Behringer)

Denmark

At least 1,000 executed

Matthew Hopkins, the self-proclaimed Witchfinder General; the vulnerable old widow accused of witchcraft; confessions elicited under torture; mob justice. It’s easy to believe the sensationalist portrayals of the witch hunts and witch trials of 16th and 17th century Europe.

But what do we really know about witch trials in early modern Europe?

Inspired by an interest in gender and crime in Germany, Professor Alison Rowlands is challenging the popular myths, misconceptions and stereotypes.

Life in early modern Europe

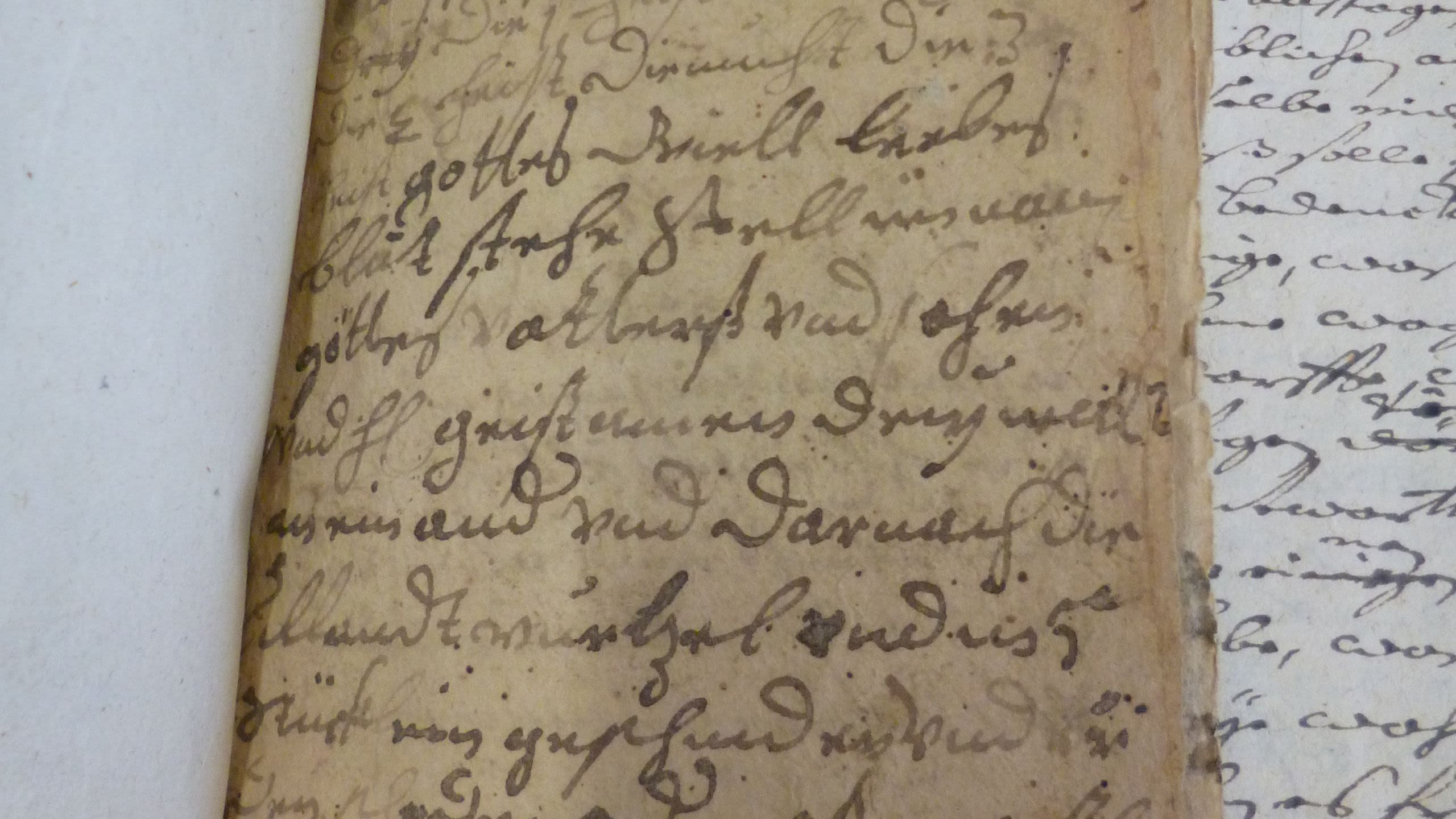

As a PhD student, Alison studied the connections between gender and crime in the German city of Rothenburg ob der Tauber and its rural territory between 1500 and 1618. She was surprised to find that only three people had been executed for witchcraft in its history, shattering what she thought she knew about the early modern ‘craze’ for witch hunting and Germany’s reputation as its heartland.

It sparked a commitment to uncovering the truth, which meant she had to understand what it was like to live in early modern Europe.

“Because we don’t believe in witchcraft now there’s a tendency to assume witch trials were about something other than witchcraft; that money, poverty or misogyny were the root cause.

“But people really did believe in witches, the devil and evil magic and we have to take that belief seriously if we are to understand what caused people to accuse others of witchcraft.”

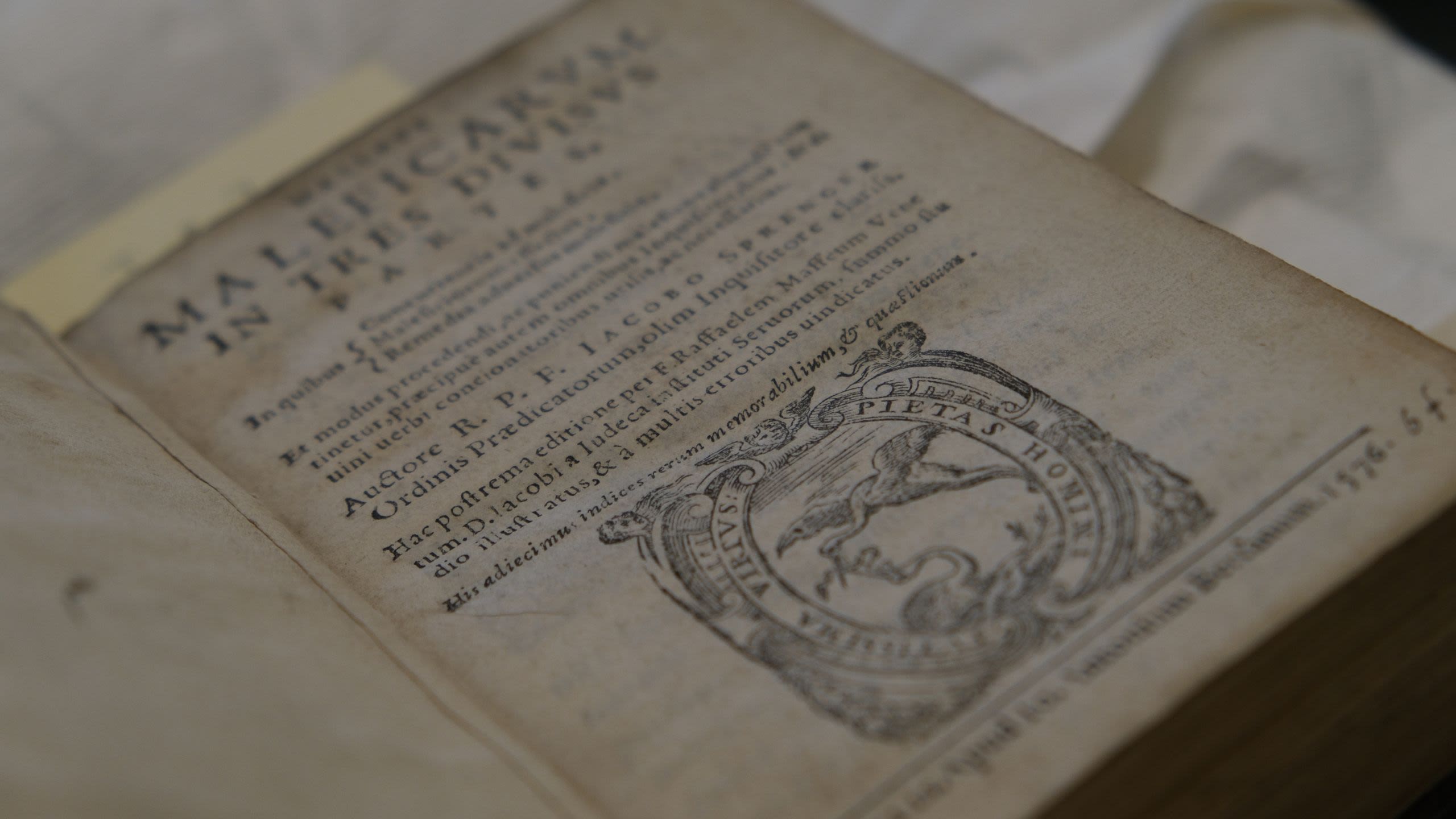

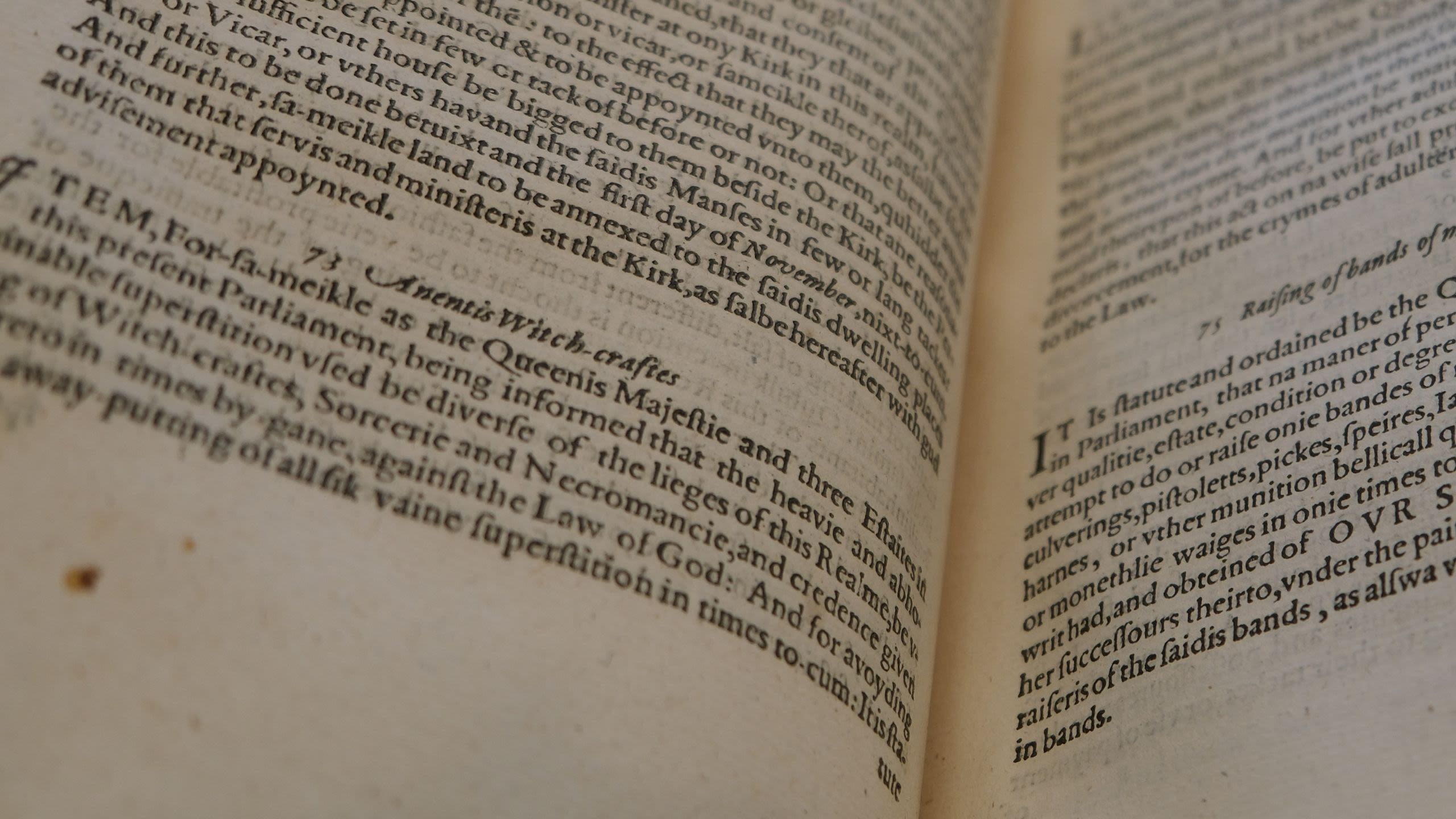

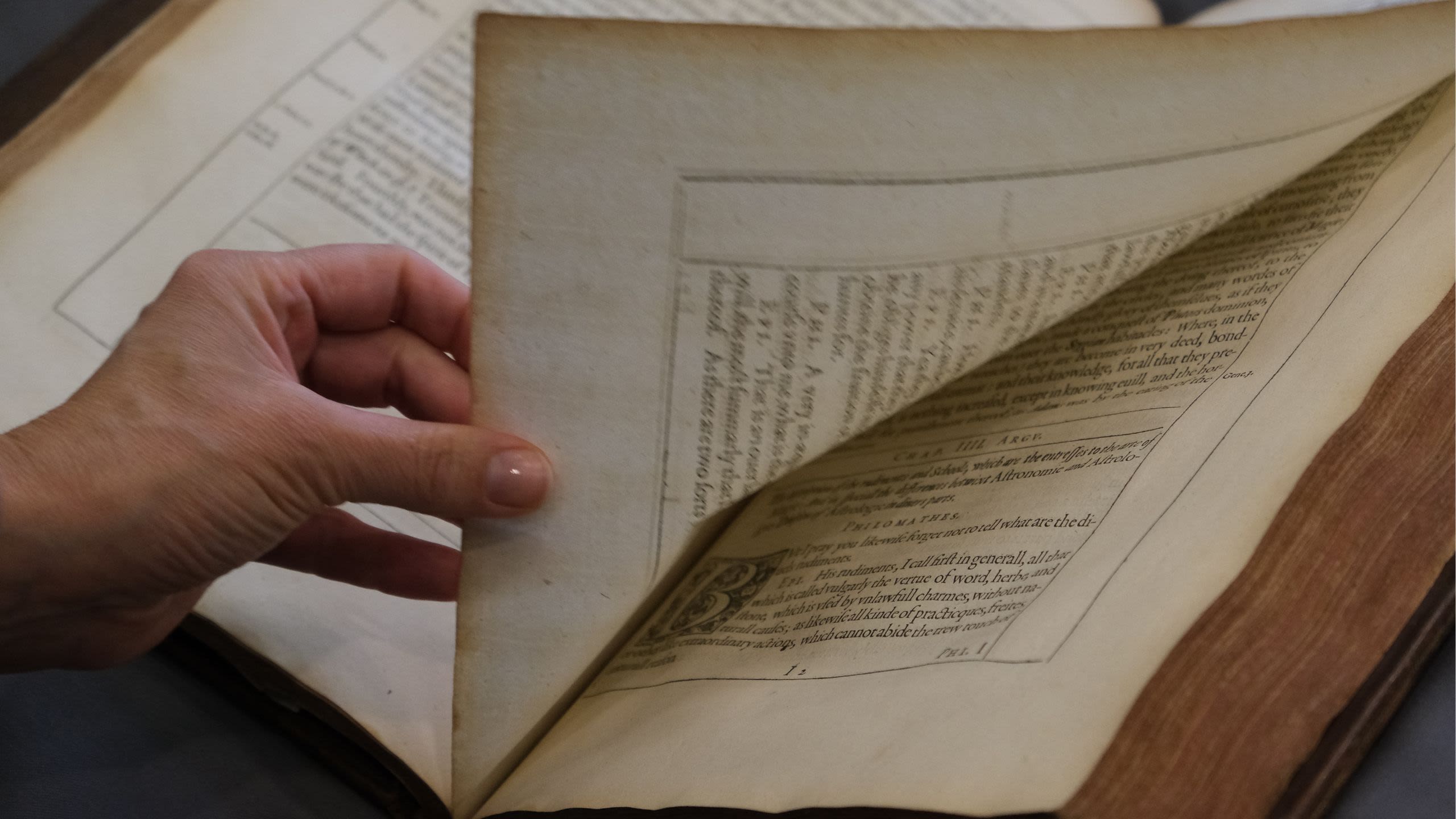

Though some have argued that contemporary texts like the infamous Malleus Maleficarum, known as The Hammer of Witches, and King James VI’s Daemonologie fuelled early modern witch hunting, Alison argues they were less influential than we may think.

Instead, she argues it was the belief in and fear of witches, coupled with the passing of laws against witchcraft, and patriarchal structures which made it easier to imagine women as witches that really drove the phenomenon. Even then, there usually had to be a specific local factor to trigger a prosecution and the broader context of life in early modern Europe also played a part.

“Religious tensions caused by Protestant and Catholic Reformations and poor weather caused by the Little Ice Age really affected how people experienced their world.

“Ordinary people were concerned about their livelihoods and food supplies, while heightening awareness of the devil and the idea that witches were in league with him made people fearful, and vulnerable.

“If you put yourself into the shoes of an early modern European, it’s easy to believe that a ‘bad neighbour' – someone who transgressed the norms of Christian communal living – could be a witch working against you.”

What Alison’s work on Rothenburg ob der Tauber revealed was that despite these conditions, the picture wasn’t straightforward and some regions could resist the pressure to prosecute witches.

“Despite popular perceptions, large-scale witch persecution was not the norm and many communities learned from bitter experience how damaging large-scale witch trials could be.”

Professor Alison Rowlands

Revealing the truth

Alison’s book Witchcraft Narratives in Germany: Rothenburg, 1561-1652, was the first academic study of witch trials in this region, making a key contribution to historical understanding.

In it, she analysed the gendering of witch persecution, detailing case-studies of trials involving men and children.

Although statistics show that in some countries over 90% of those accused of witchcraft were women, the percentage in other countries was lower, with on average 20-25% of those accused being male. This demonstrates that the picture is far from clear cut.

Alison’s research papers have critically analysed the stereotype of the witch as an old, poor woman, demonstrating instead that a much wider range of people were imagined as witches, and her later work has focused on male witches and the issue of masculinity.

She has shown that it wasn’t just gender that varied by region, different laws and beliefs have also impacted what we think we know, and even misled people into arguing that English witch trials were somehow exceptional.

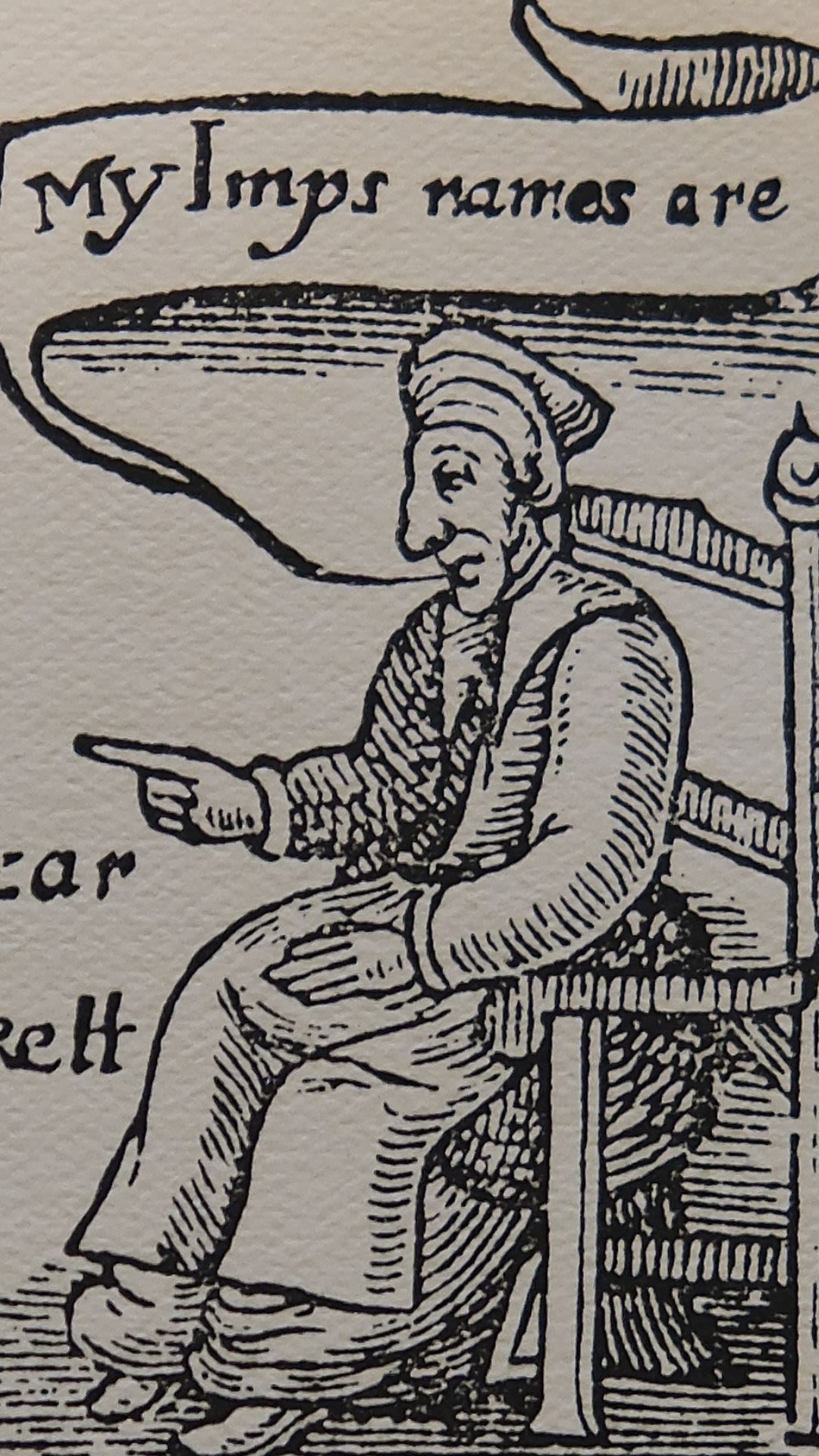

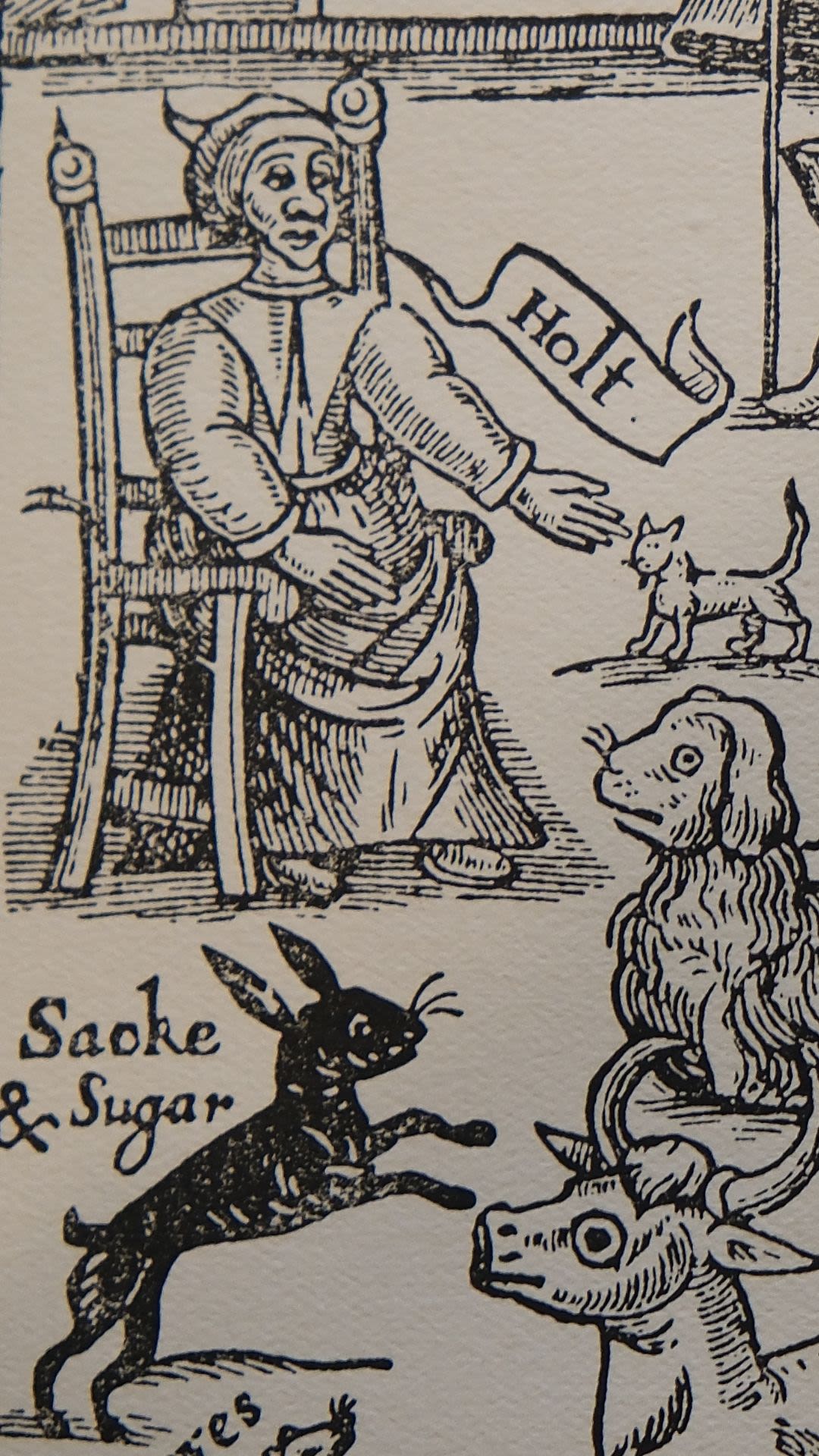

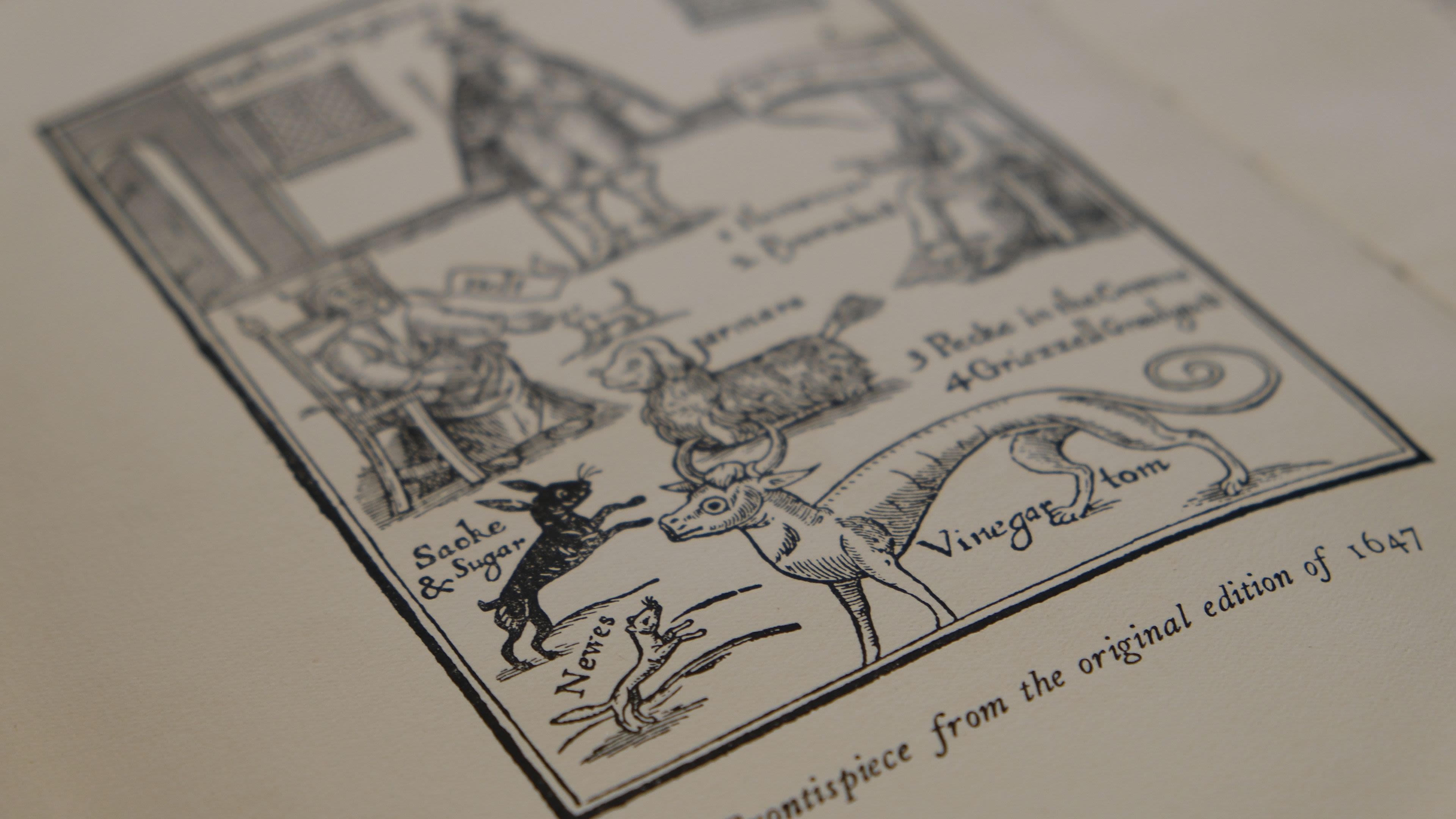

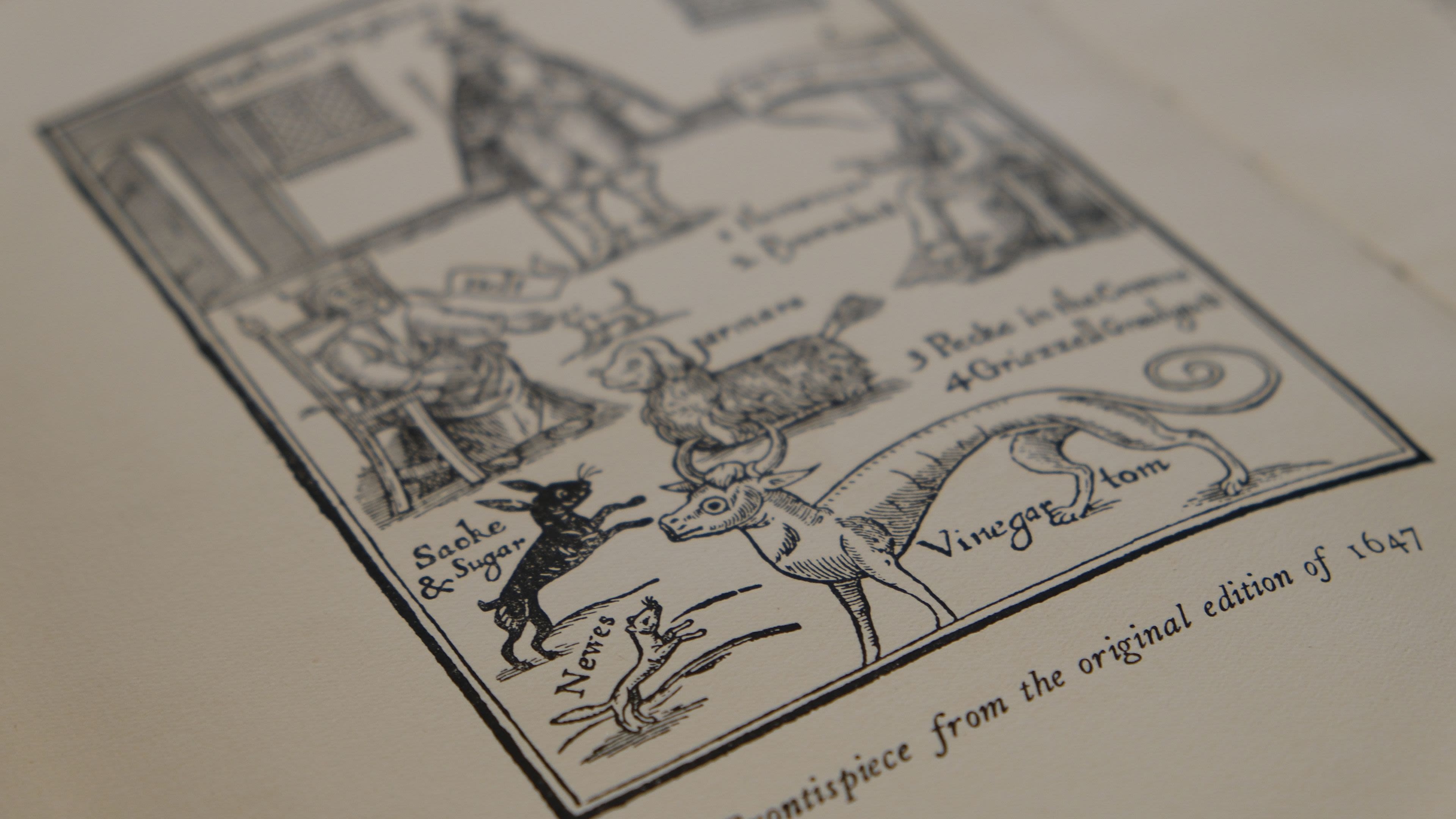

“England had a different legal system to the rest of Europe which didn’t technically allow torture, but we know that sleep deprivation was used to force confessions out of suspects in the East Anglian witch trials of 1645-1647,” she explained.

“In England too there were slightly different beliefs, particularly around the importance of a witch’s relationship with a familiar – a demonic imp in the form of an animal.

“These differences have been overplayed in the past but we now know that the English witch trials were really just another European variant and not exceptional.”

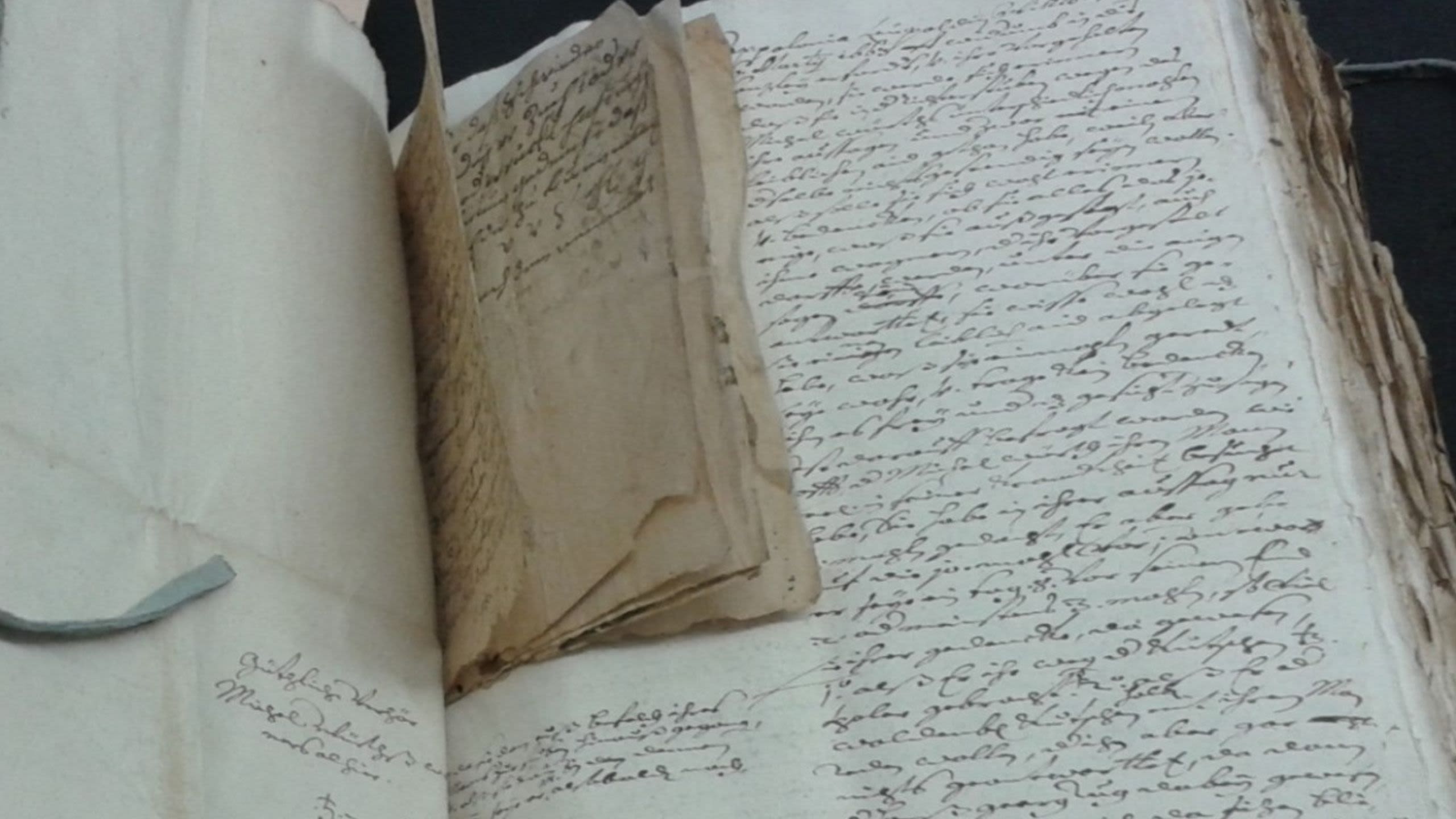

Today, Alison’s research focus is Michael Wirth, a wheelwright from Rothenburg who was accused of murder by witchcraft in 1663. Thanks to incredibly detailed historical records made at the time, she is reconstructing his family history and tracking how the trial affected him, his wife and their children in the decades after.

Changing perceptions

Through school outreach and public engagement, Alison has changed perceptions around the history of witchcraft in both Germany and Britain.

She has worked with school pupils from primary schools to sixth forms and developed a training pack for teachers which is available nationwide. Extracts from her book, Witchcraft Narratives in Germany, have even been included in exam papers.

One teacher, from St Benedict’s Catholic College in Colchester, said after working with Alison: “[The students] really loved the unit and your podcasts…so much so that we’ve included it in the scheme of work for future years.”

In 2024 she worked with sixth-form students at Brentwood Ursuline Convent High School where she led workshops on the Bamberg Witch craze of the 1620s and the East Anglian witch trials. Together they analysed contemporary sources and explored the reasons for persecution in the context of 17th century society.

Feedback from her numerous public lectures and family workshops has been overwhelmingly positive, with the Chair of the Essex Branch of the Historical Association confirming that those present at one event “derived a new understanding of the previously enigmatic East Anglian witch hunts.”

“The students found Alison’s workshops highly stimulating and excellent preparation for their A Level studies and examinations.”

Darren Earle

History and Politics Teacher, Brentwood Ursuline Convent High School

Remembering the Essex victims

Essex had an unusually large number of witch trials compared to other English counties, with nearly 300 people, mainly women, tried at Chelmsford’s Assize Courts between 1560 and 1680. The largest witch trial in English history, in which the ‘witch finders’ Matthew Hopkins and John Stearne made their names, also began in Essex, in 1645. Alison has made an unprecedented contribution to how we remember the victims of these witch trials.

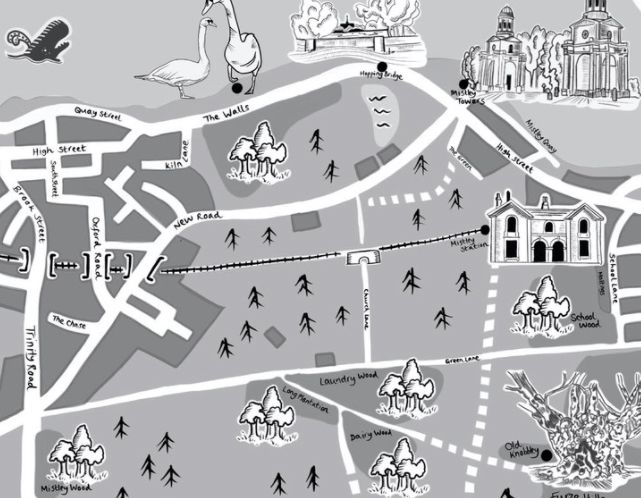

In 2022 she was historical adviser on the creation of a new walking tour around Manningtree and Mistley commemorating the lives of the 36 Essex women accused in 1645, nineteen of whom were executed. It featured stories and poems written by local women from the perspective of the victims, imaginatively recreating their life stories and experiences.

She is also historical consultant on a Tendring District Council project to erect information boards and benches at Manningtree and three other locations in the Tendring Hundred associated with some of the most severe Essex witch trials.

Funded by the Rural England Prosperity Fund, the project will include augmented reality and web content complementing the on-site information.

Alison has been key to identifying the right locations and which individual stories – accused witches, accusers and legal officials – to tell.

"Alison's work has been hugely influential in the work we do here. "

Ben Paites

Collections and Learning Curator, Colchester and Ipswich Museums

Find out more

Follow the Manningtree witch walk

Manningtree in north Essex was the centre of England's largest witch trial, which began in 1645. Follow the local walk, co-developed by Professor Rowlands, to find out more about the victims.

Research that challenges

Our School of Philosophical, Historical and Interdisciplinary Studies fosters a distinctive research ethos that aims to question and disrupt received ‘truths’ about the past and present. Find out more.

Sixty Stories

We’re celebrating 60 years of making change happen. 60 years of boldness and bravery from our students past and present. 60 years of creating change.