Saving tattoo art

Losing the irreplaceable collections of trailblazing tattoo artists and body modification pioneers would deprive us of vital insights into our culture and history.

Inspired by a family cautionary tale, Dr Matt Lodder has dedicated his personal and professional life to piecing together and celebrating the history of tattooing.

By saving, studying and exhibiting rare tattoo collections, Dr Lodder has ensured tattoo art gets the recognition it deserves.

Hooked on tattoos

“My great-grandmother was tattooed by her brother in the early 20th century. He told her it would wash off, which of course it didn’t!”

This cautionary family tale and a childhood obsession with the tattoos of 1980s rock stars and WWF wrestlers set Dr Matt Lodder on a personal and professional path that has transformed the appreciation and understanding of tattoo art and the tattoo industry.

“I was hooked almost instantly. I became a historian in order to learn more about this practice which fascinated me so much and I think the fact that I was a tattoo collector first and a historian second has been an important part of my professional work,” he explained.

From PhD student to prominent and influential tattoo historian, Matt has carved out a new sub-discipline within the world of art history research, teaching and curating.

His two solo-authored books, Painted People: Humanity in 21 Tattoos (2022) and Tattoos The Untold Story of a Modern Art (2024) have transformed public and academic understanding of the artform, which is now a multi-million dollar global industry.

His work on exhibitions at the Museum of London, the National Maritime Museum and our own Art Exchange have traced the history of tattoos and tattooing, challenged myths and given public audiences a glimpse of what Matt describes as a “magical, romantic, exciting and often misunderstood artform.”

Matt’s most enduring contribution however is the three private collections that he has saved from destruction and dispersion, preserving critical pieces of tattoo history for future generations.

“We can understand people and places from the images they make, and that is particularly true if we look at the intimate art people wear on their skins.”

“Tattoos give us unique insights into people and (sub-)cultures which aren’t otherwise often well represented in places like museums and archives.”

Dr Matt Lodder

“Tough, well-respected and funny as hell”

Jessie Knight was born in 1904, into an eccentric family with a proud tattooing heritage. When her tattoo artist father decided to take his sharp shooting circus act as Two Guns Rix on the road, she took over his Barry Island tattoo parlour, at the age of 17.

She would become Britain’s most prominent female tattoo artist of the 20th century.

“Jessie’s work is energetic. It has an authenticity to it, particularly the way she draws women. She draws a lot of the standard tropes, like sexy pin-ups, but her sexy pin-ups all have really vicious faces and scowls. Her work is full of humour and personality,” explained Matt.

That humour shone through in her tattoo parlours in Barry, Chatham, Aldershot and then Portsmouth, where she would draw on the lyrical genes of her grandmother, a greetings card poet, and write her shop signs in verse:

“Tattoos on a lady are apt to be shady.”

“If you’re one over the eight, you’re too late.”

By the 1950s, Jessie was one of Europe’s most famous and important tattoo artists, with connections across the continent and the USA.

In 1955, she was awarded second place in the Champion Artist of All England competition with a full-back colour depiction of a highland fling. Though a woman in a very male-dominated world, it’s clear she was respected and rated by her peers.

“She was tough, well respected and funny as hell,” said Matt.

By the 1970s, she had retired and was living back in Barry Island where she died in 1992.

Matt had long been fascinated by Jessie and when he was starting work on what would be a ground-breaking exhibition at the National Maritime Museum in Falmouth, he was reminded of a passage in the 2002 autobiography of another tattoo artist, Ron Ackers:

“When tattooing, she [Jessie] used to sit on a big old trunk, rather like a wooden seaman’s trunk…Naturally, she was always being asked what was inside the trunk and she’d reply ‘one day I’ll show you.’ When that day came, when she was prepared to show me what was in the trunk, I found it was full of old tattoo designs, old machines, old photographs and other bits and bobs associated with tattooing.”

Although the trunk itself was long gone, using his networks in the tattooing community, Matt traced Jessie’s nephew, who had kept its contents.

“She’d had that trunk since she’d first started tattooing in the 1920s and it went everywhere with her. She had collected over 1,000 individual items including all her designs and all the paraphernalia, ink-stained towels and sticky notes saying things like 'find me in the pub', tattoo machines, ink bottles, used and unused needles,” explained Matt.

As well as her own items, Jessie had kept her father’s collection, dating back to the 19th century and charting the history of tattooing not just in the UK but in the USA as well. The pièce de resistance was a beautiful oil-painted banner painted by Alexander Colville Gordon, which she had hung in all her tattoo parlours.

The family loaned the collection to Matt for his Falmouth exhibition where some items went on show for the first time – more were later exhibited at the University’s Art Exchange. When the oil-painted banner was sold to a private collector, Matt was determined to save the rest and helped to negotiate a deal with the Museum of Wales to ensure its preservation.

“This is the only collection of its kind. There’s nothing else like it in any public museum. It’s as if she packed up her shop one day and put everything into that trunk as she found it, all the ephemeral items like scraps of paper, pictures with sticky back plastic on them, dirty rags. And everything was covered in cigarette smoke and graphite dust,” Matt said.

Museum experts, who are hoping to stage a major exhibition of the collection in 2027, have had to develop new conservation techniques for Jessie’s unique collection.

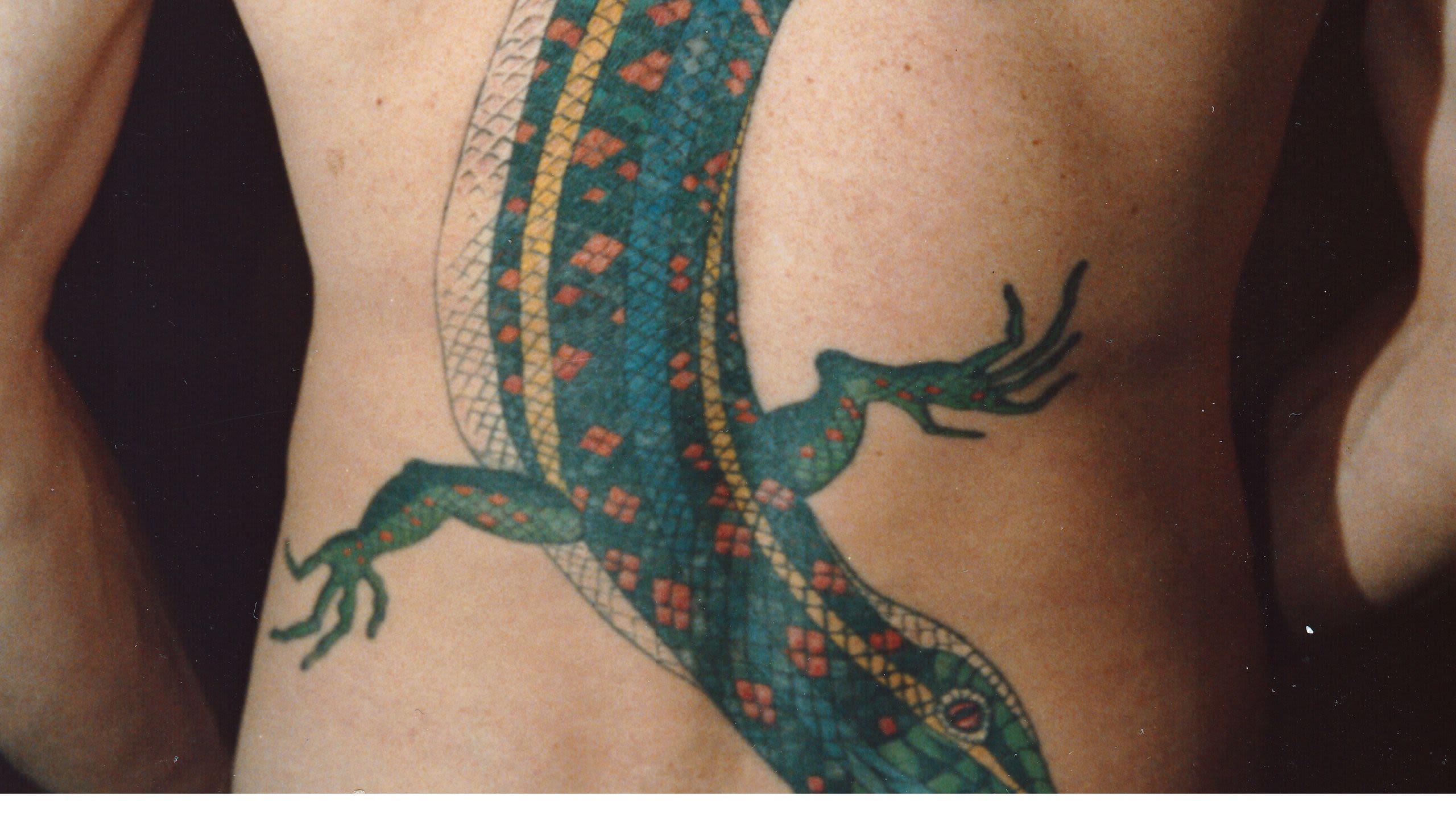

A tattoo design, by Jessie Knight, courtesy of the Museum of Wales

A tattoo design, by Jessie Knight, courtesy of the Museum of Wales

Jessie Knight, tattooing a client, courtesy of the Museum of Wales

Jessie Knight, tattooing a client, courtesy of the Museum of Wales

Items from the Jessie Knight collection, courtesy of the Museum of Wales

Items from the Jessie Knight collection, courtesy of the Museum of Wales

The notorious Mr Sebastian

Alan Oversby was a mild-mannered, erudite art teacher, born in Liverpool in the 1950s. As his alter-ego, Mr Sebastian, he would become the UK’s first tattoo artist with a fine art degree and the protagonist who enabled body piercing to go mainstream.

His life as a gay man interested in consensual BDSM (bondage, discipline, dominance and submission, sadomasochism) led him to train in California with some of the world’s greatest tattoo artists at the forefront of the body modification movement, but it would also mar his life in controversy.

A tattoo design by Mr Sebastian, courtesy of the Bishopsgate Institute

A tattoo design by Mr Sebastian, courtesy of the Bishopsgate Institute

“His designs are beautifully rendered, usually images of men engaged in excessive sexual acts. They are very graphic but also beautiful and tender. To the naïve eye, they are astonishing. He was a brilliant draughtsman,” explained Matt.

Alan set up his business in London in the 1970s after learning tattooing from gay tattooers in the USA such as Cliff Raven, and after sharing piercing knowledge with Jim Ward and Doug Molloy, the founders of the world’s first body piercing shop. His clients were mainly middle-aged and older gay men who wanted graphic tattoos that would be hidden under their clothes, often on their genitals.

He had become interested in body piercing as a student in Gyana where he saw field workers with nipple rings. By the 1970s, he was the UK’s first professional body piercer, experimenting with safer methods, sometimes on himself, and inventing and designing jewellery. By the time he was featured in the 1989 book, Modern Primitives, he had cemented his status as the UK’s foremost body piercer, albeit on the fringes of conventional society.

In 1987 Alan’s life crumbled when he was arrested as part of Operation Spanner, an investigation into same-sex BDSM led by the Obscene Publications Squad of the Metropolitan Police.

With 15 others, he was convicted of assault, setting an important legal precedent that consent was not a valid legal defence.

An unsuccessful appeal in 1994 coincided with body piercing shooting into the mainstream - after celebrities like Alicia Silverstone were pictured with belly button piercings - where it has remained.

“He was the main driver of body piercing in the UK. It couldn’t have gone mainstream without his contribution,” said Matt.

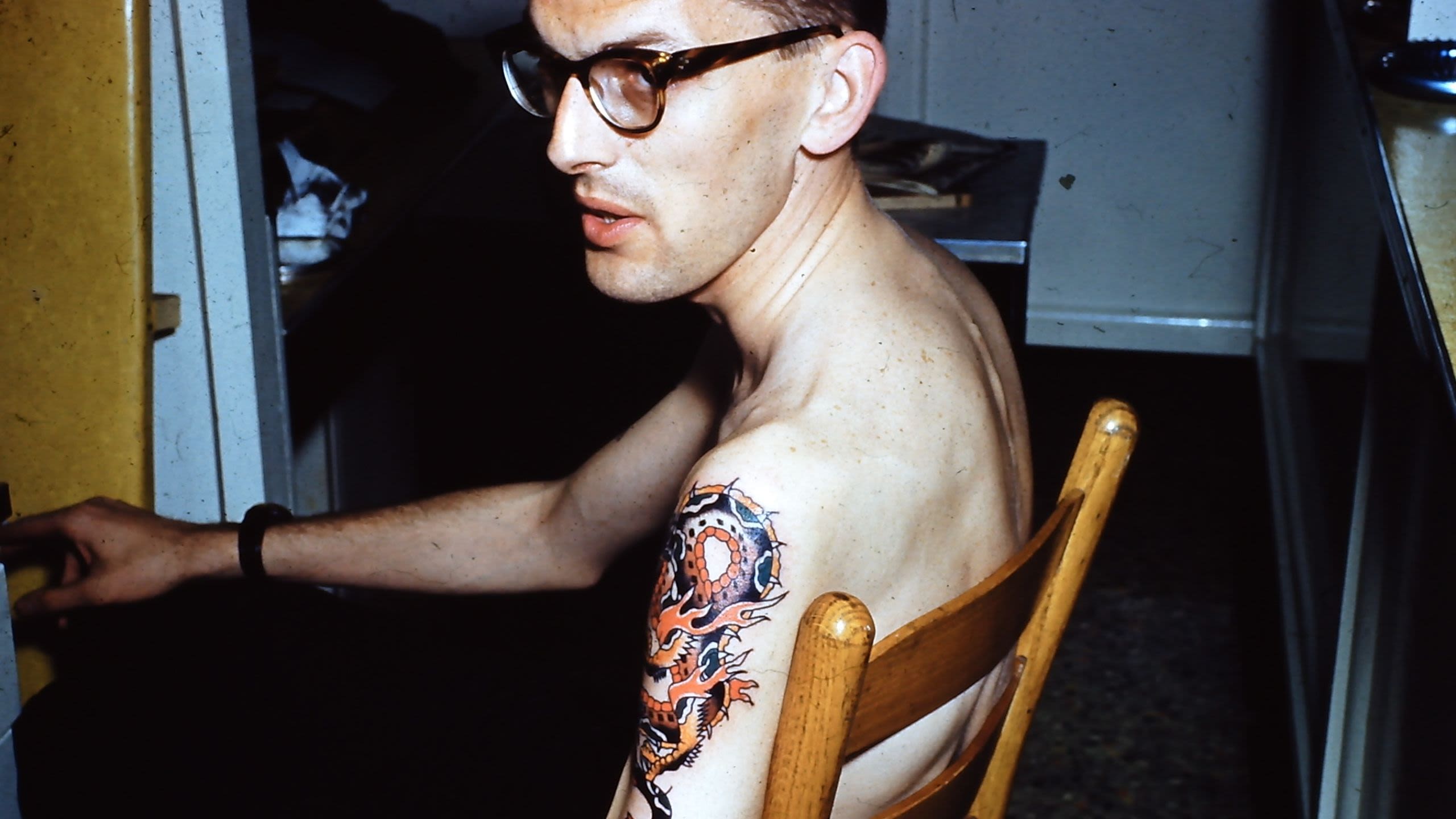

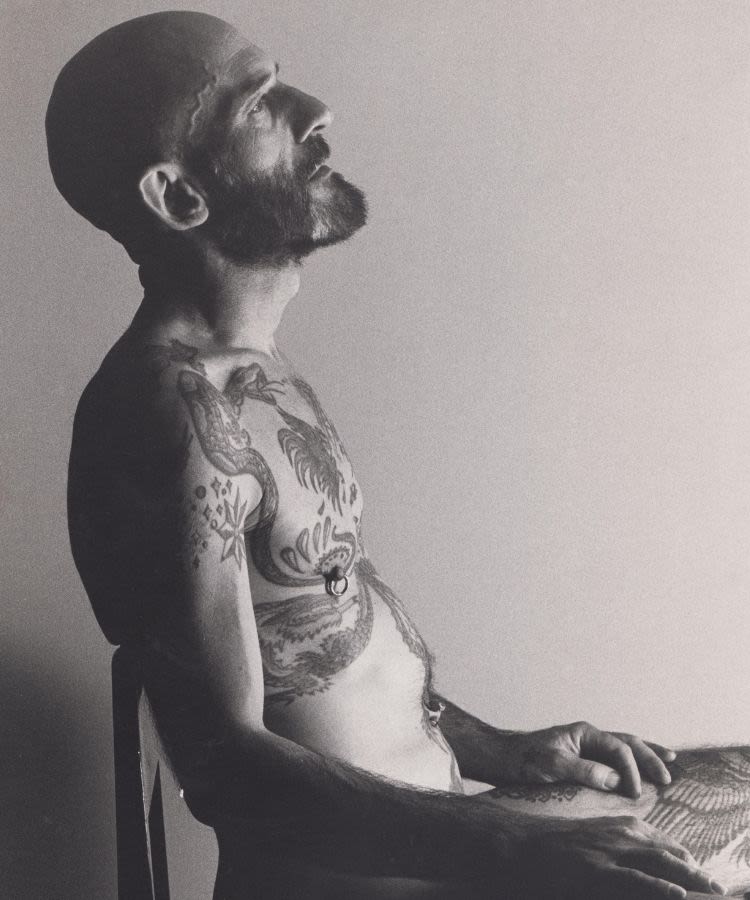

A tattoo by Mr Sebastian, courtesy of the Bishopsgate Institute

A tattoo by Mr Sebastian, courtesy of the Bishopsgate Institute

Alan died in 1995, leaving most of his possessions to an old friend. By 2022, when that friend died, Matt had established a partnership with curators at the Bishopsgate Institute, who were trying to preserve artefacts relating to Operation Spanner. Through his own networks and negotiations Matt helped secure most of Mr Sebastian’s collection for future generations, and support an exhibition of the collection in Las Vegas, researched by the director of the Body Piercing Archive in San Francisco, Paul King.

“Alan’s collection included photos, and some ephemeral pieces such as sculptures, letters, lots of drawings and stencil sheets, even pillows stuffed with the pubic hair shaved off his clients and returned evidence bags that had been seized during Operation Spanner.

“It tells us something really important about cultural life. If you think of tattooing in London in the 1980s, you’d probably think of skinheads or football hooligans, but Alan’s photos show these beautifully rendered, full-back pieces in single point dot work. It’s not the kind of thing you imagine and it was all hidden away under clothing, it hasn’t been seen before,” explained Matt.

The “linchpin” of the 20th century tattoo industry

Rudi Inhelder was a gay, Swiss physicist, working for the USA’s Cold War defence industry and an avid tattoo fan. He amassed Europe’s largest collection of documents relating to the international tattoo industry and was instrumental in creating the foundations of the modern-day tattoo industry.

He had become fascinated by tattoos and tattooing after reading a history of the industry, Pierced Hearts and True Love by Hanns Ebensten. When he came to London in 1955, it was Ebensten that Rudi gravitated towards and who connected him with other tattoo enthusiasts and artists.

After travelling to America for work, Rudi longed for the “camaraderie, connection, and companionship of tattooers and tattooed people that he had found in London,” Matt explained.

Hans Rudolf (Rudi) Inhelder, courtesy of Dr Matt Lodder

Hans Rudolf (Rudi) Inhelder, courtesy of Dr Matt Lodder

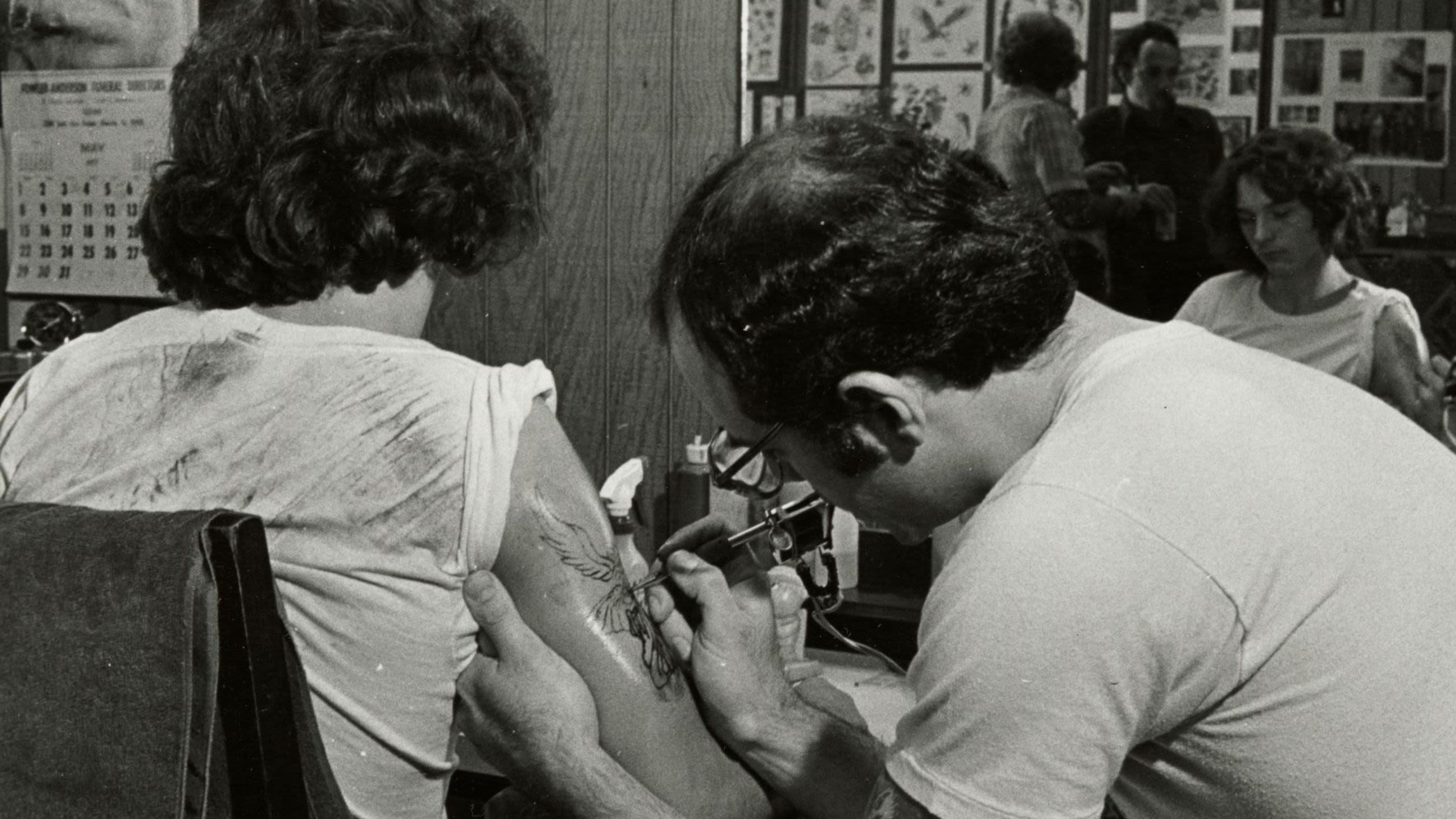

It was there, in 1963, that Rudi founded the ground-breaking Tattoo Club of America.

Despite tattooing being illegal in New York at the time, the Club flourished and although ultimately short-lived, by 1964 it had 250 members, mostly men, and was regularly publishing tattoo newsletters.

As well as giving artists and fans the opportunity to meet, the Club, which collected information about interests from its members, also served as a clandestine match-making service for the many gay men, like Rudi, who wanted to meet other gay men and swap tattoo photos.

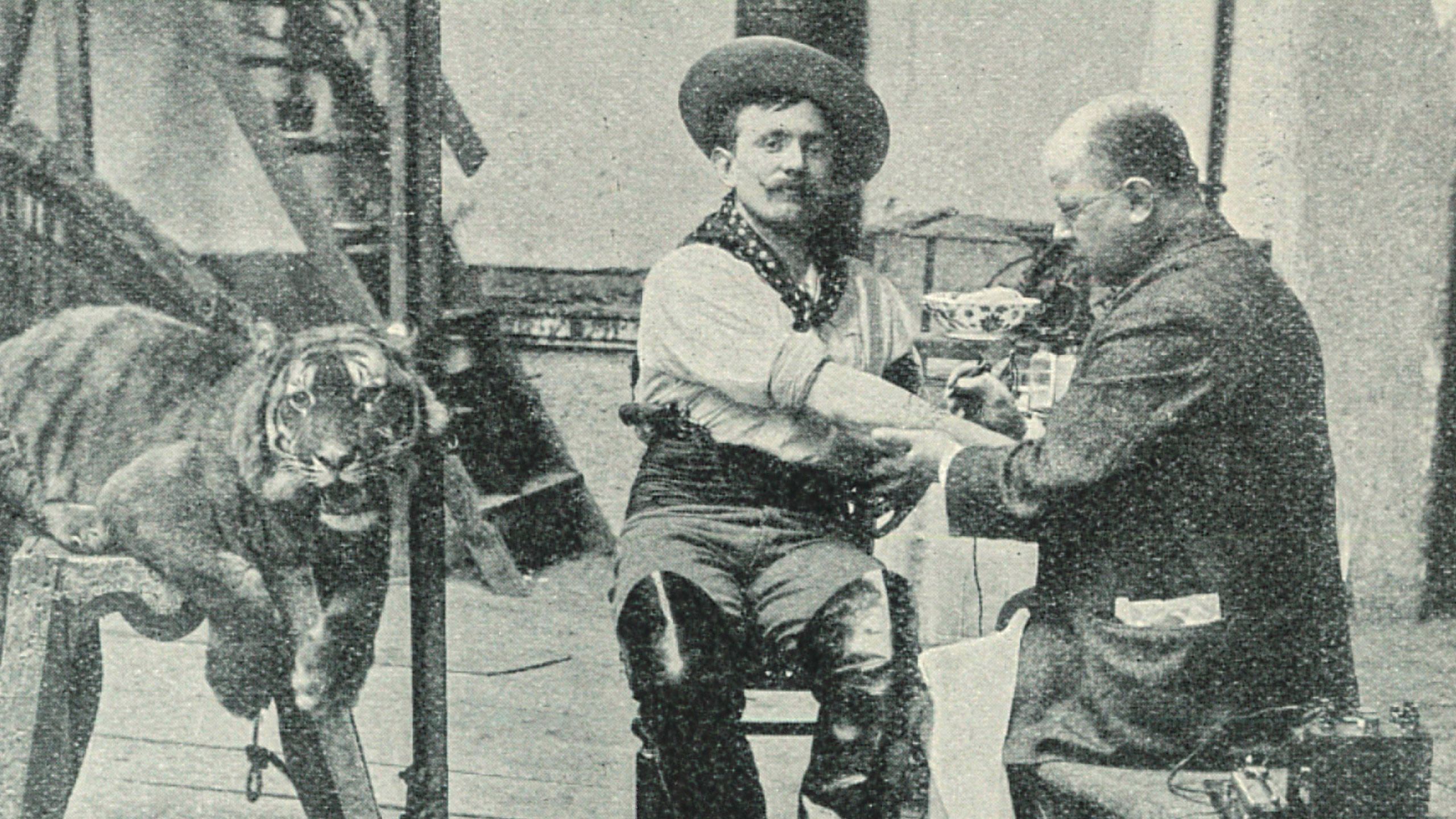

A tattoo artist working in the 1970s, courtesy of Oakland Museum of California

A tattoo artist working in the 1970s, courtesy of Oakland Museum of California

“Rudi’s network encompassed the whole spectrum of the industry. Members spanned conservative, battle-hardened military tattooers through to radical and queer experimenters. His innocently presented networking provided a way for queer men to meet likeminded others from outside their local towns in relative safety.

“Though he wasn’t a tattoo artist, Rudi would become this absolute linchpin. He connected European, British, and American tattooing, and was instrumental in friendships and working relationships between mainstream and rather conservative tattooers and a diverse group of subcultural tattoo and body-piercing enthusiasts,” said Matt.

Much of Rudi’s vast collection was destroyed after his death in 2003 but Matt was determined to save what remained.

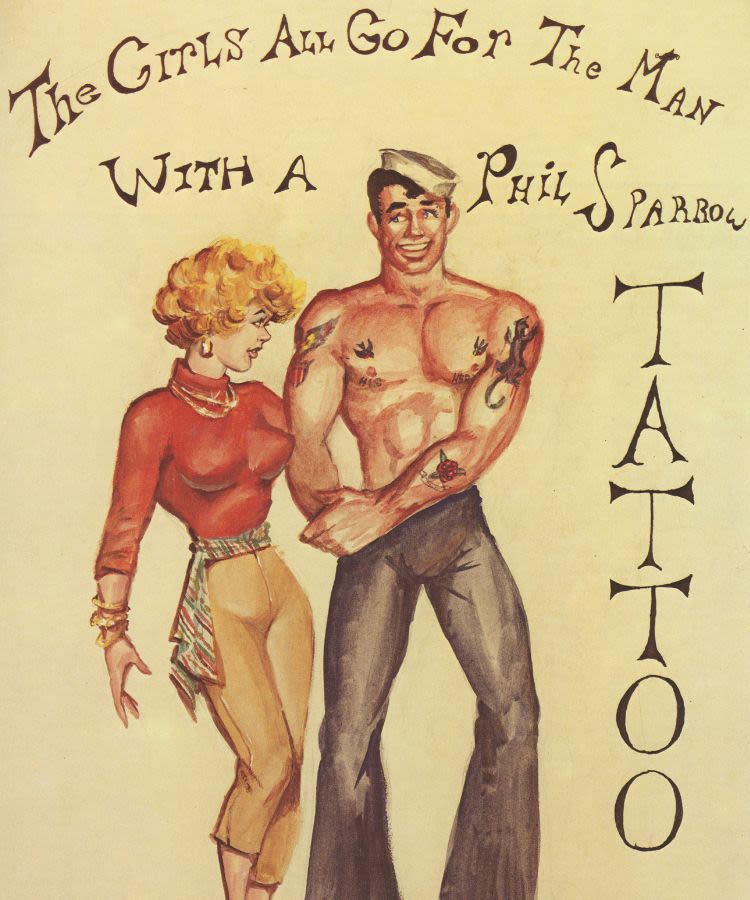

An advertising flyer, courtesy of the Body Piercing Archive

An advertising flyer, courtesy of the Body Piercing Archive

Working with Paul King, from the Body Piercing Archive in San Francisco, and Manfred Kohrs, of the German Tattoo History Institute, he pieced together the surviving traces of Rudi’s influence and finally located what was left of Rudi’s collection to his family home in Switzerland. The numerous photos and business cards, and Rudi’s meticulous record-keeping, revealed the extent of his links.

“Those links underpinned the direction western tattooing would take over the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, and the interconnections between tattooing and the emergent body-piercing industry,” said Matt, who has negotiated for the collection to be preserved alongside the Mr Sebastian collection at the Bishopsgate Institute.

“All of these collecting acts are interconnected because Rudi and Alan knew each other and knew most of the same people, like Jim Ward in West Hollywood. Jessie is a step further removed but they are all part of one community and all hugely influential to the story of 20th century tattooing.”

Dr Matt Lodder

Find out more

Dr Matt Lodder explains what we can learn from studying tattoos and tattoo history.

Find out what art history courses are on offer through our School of Philosophical, Historical and Interdisciplinary Studies.

Sixty Stories

We’re celebrating 60 years of making change happen. 60 years of boldness and bravery from our students past and present. 60 years of creating change.