Fighting for the rights of the Innu

Who are the Innu?

The Innu are a thoughtful and respectful indigenous people, who were permanent nomadic hunters of the eastern Labrador-Quebec peninsula in Canada.

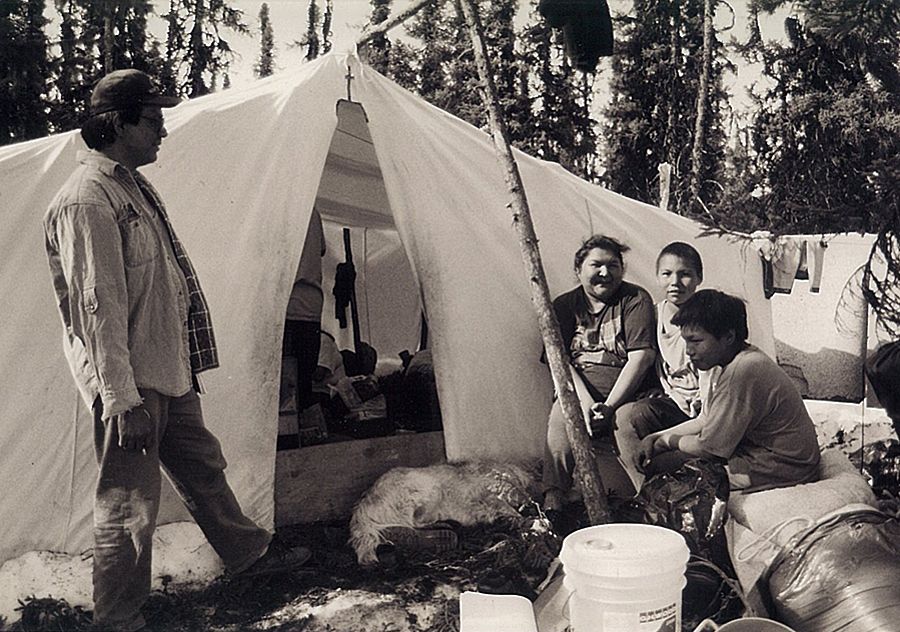

Picture courtesy of Professor Colin Samson

Picture courtesy of Professor Colin Samson

They were an incredibly resilient people, who successfully lived in one of the most demanding habitats on the planet. They hunted and fished, but mainly relied on the caribou which migrated through their land every spring and autumn.

Their heritage is a deep connection with and concern for the land, but they have never presumed to own it.

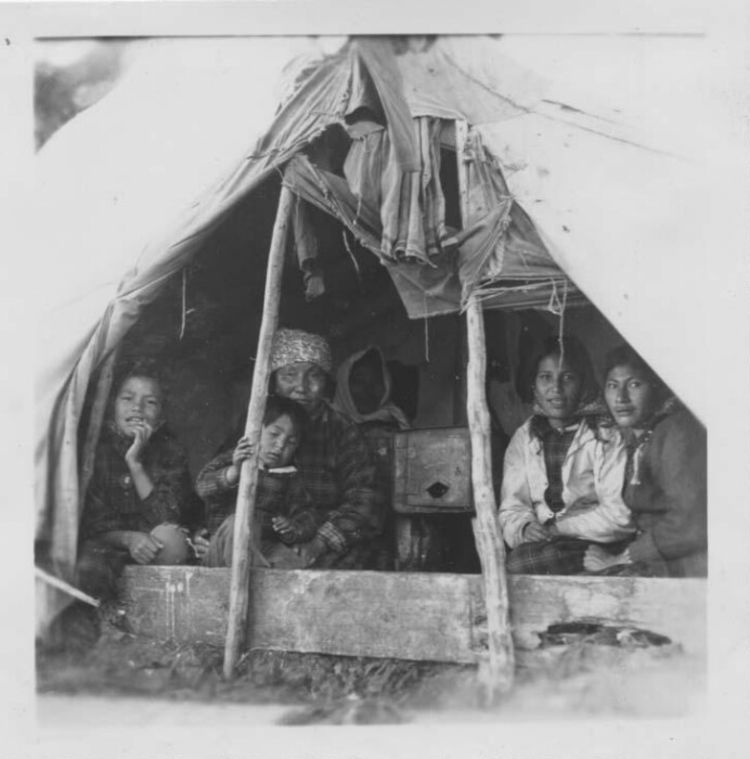

Picture courtesy of Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum

Picture courtesy of Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum

But all that changed in the 1950s and 1960s when the Canadian government started an aggressive campaign to force the Innu from their land into fixed settlements and, for a time, criminalising their way of life.

This transition to a new, alien lifestyle, left the Innu traumatised and many fell victims to social and psychological problems common to other colonised indigenous peoples such as alcoholism, drug abuse and record levels of suicide.

Documenting the horror of being unsettled

Professor Colin Samson, from our Department of Sociology and Criminology, first got involved with the Innu after being commissioned to co-author a human rights report with Survival International.

The landmark report - Canada’s Tibet - documented the link between the Canadian government’s policies of forced assimilation and land claims with the social suffering in the Innu communities.

Winning the 2000 Pio Manzo Peace Prize, the report has become an acknowledged international support for the Innu in their conflicts with the Canadian government and their struggles to maintain their own distinctive way of life.

This report sparked the beginning of a research journey spanning more than 30 years, with Professor Samson working to raise awareness about the shocking power imbalance between the Innu and the Canadian government and their fight to get justice.

After writing the human rights report, Professor Samson soon realised that it was important not to just document the suffering and trauma, but to look at how it could be addressed by showing the positive side of maintaining their way of life.

“Understanding the relationships between the Innu and their land has been at the heart of my research,” explained Professor Samson.

“In my observation, when the Innu people were on the land, doing Innu land-based things they were healthier; they were happier.

"This is one of the positive things they are doing to deal with the disfunction that has been forced upon them.”

Special bond of friendship

When Professor Samson first stayed with an Innu family in 1994 the bond he felt to these people was immediate.

Over the years, this has developed into lifelong friendships with many Innu people.

“Because of their situation and because of the suffering that I could see all around me in the communities, I realised that my research couldn't be done at arms-length.

“My research had to be with them, not on them, and that's how I proceeded.”

Since then, he has shown that one of the most important determinants of health is the ability of people to practice their own culture, speak their own language and be on the land where they find meaning and purpose and are not troubled by the serious issues plaguing their community.

Global platform for plight of indigenous people

A resilient attachment to the natural environments which they call home is key for indigenous communities around the world.

As the world’s last remaining natural resources become ever-more valuable, the exploitation of their lands, forced assimilation, and even the risk of poisoning from extractive projects made in the name of ‘progress’ are the realities for indigenous people in North America.

Professor Samson has also worked with groups fighting resource extraction projects including the Dakota Access Pipeline at the Sioux Standing Rock reservation in the US and the Muskrat Falls dam affecting the Innu in Canada.

In 2004 Professor Samson made a statement at the UN Working Group on Indigenous Peoples in Geneva, where he explained the history of the Innu and the acts of cultural and physical extinguishment of the people.

After writing a brief for UN Special Rapporteur Rudolfo Stavenhagen, in 2005, the UN Human Rights Committee requested that Canada alter its extinguishment policy in its subsequent ‘country report’ on Canada.

In collaboration with organisations including Amnesty International and the American Indian Law Resource Center, Professor Samson was also part of an international fact-finding mission on land rights of the Innu of Matimekush, Quebec in 2007.

They interviewed elders and community members on their experiences of forced relocation to this area, environmental damage from the iron ore mining and the unilateral extinguishment of their land rights. These interviews have been used in several of Professor Samson’s research publications.

Same fight ... but new aggressor

Today the Innu are facing a new threat to their land – imposters.

The number of false claims of indigenous heritage – whether for professional, financial or other reasons – appear to be growing around the world.

And Canada is no exception.

Professor Samson has been supporting the Innu in this new threat to their home – which prompted indigenous leaders to hold an Identity Fraud Summit in Winnipeg in May 2024.

The aggressors are the NunatuKavut Community Council (NCC), a group the Innu had always regarded as white Canadians – settlers descended from mostly British migrants. Over the past two decades, the NCC has advanced a sophisticated and well-funded claim to belonging to an Indigenous group known as “Southern Inuit” – or more recently, simply “Inuit”.

In 2019, the NCC signed a memorandum of understanding with the Canadian government, opening up the potential to claim rights to swathes of land that have been central to the Innu way of life for thousands of years, even though Canada has repeatedly rejected NCC’s claims previously for lack of evidence.

This land is also of huge interest to mining and hydro-electric power companies, making rights to it potentially very valuable.

The NCC has repeatedly refuted any suggestion that its Indigenous claims are false.

In June 2024, although a court guaranteed the NCC no indigenous rights, the Innu Nation’s contesting of Canada’s MOU with the NCC was declared unsuccessful.

Afterwards, land claims negotiator George Rich said: “Looks like whites win another round.”

Film footage courtesy of NUTAK - Memories of a Resettlement: Sarah Sandring, Nirgun Films

Find out more

Department of Sociology and Criminology

Ranked 1st in the UK for research environment in sociology (Grade Point Average, REF 2021).

Work with world-leading scholars

Department of Sociology and Criminology academics are experts in their fields, developing new approaches to understand the dynamics of social life.

Sixty Stories

We’re celebrating 60 years of making change happen. 60 years of boldness and bravery from our students past and present. 60 years of creating change.