A new approach to drug policy

Responding to the illicit drug trade is one of the biggest social challenges in the modern world and existing punitive policies aren’t working.

Essex’s Julie Hannah is playing an integral role in reversing perceptions and changing approaches to drug policy – helping millions of people caught up in the collateral damage caused by punitive drug prohibition.

New international human rights guidelines developed in partnership with the United Nations are helping governments and lawmakers to reform laws and policies to promote and protect public safety, public health, and human rights outcomes for communities around the world, including those most disadvantaged or harmed by punitive responses.

A starting point for reform

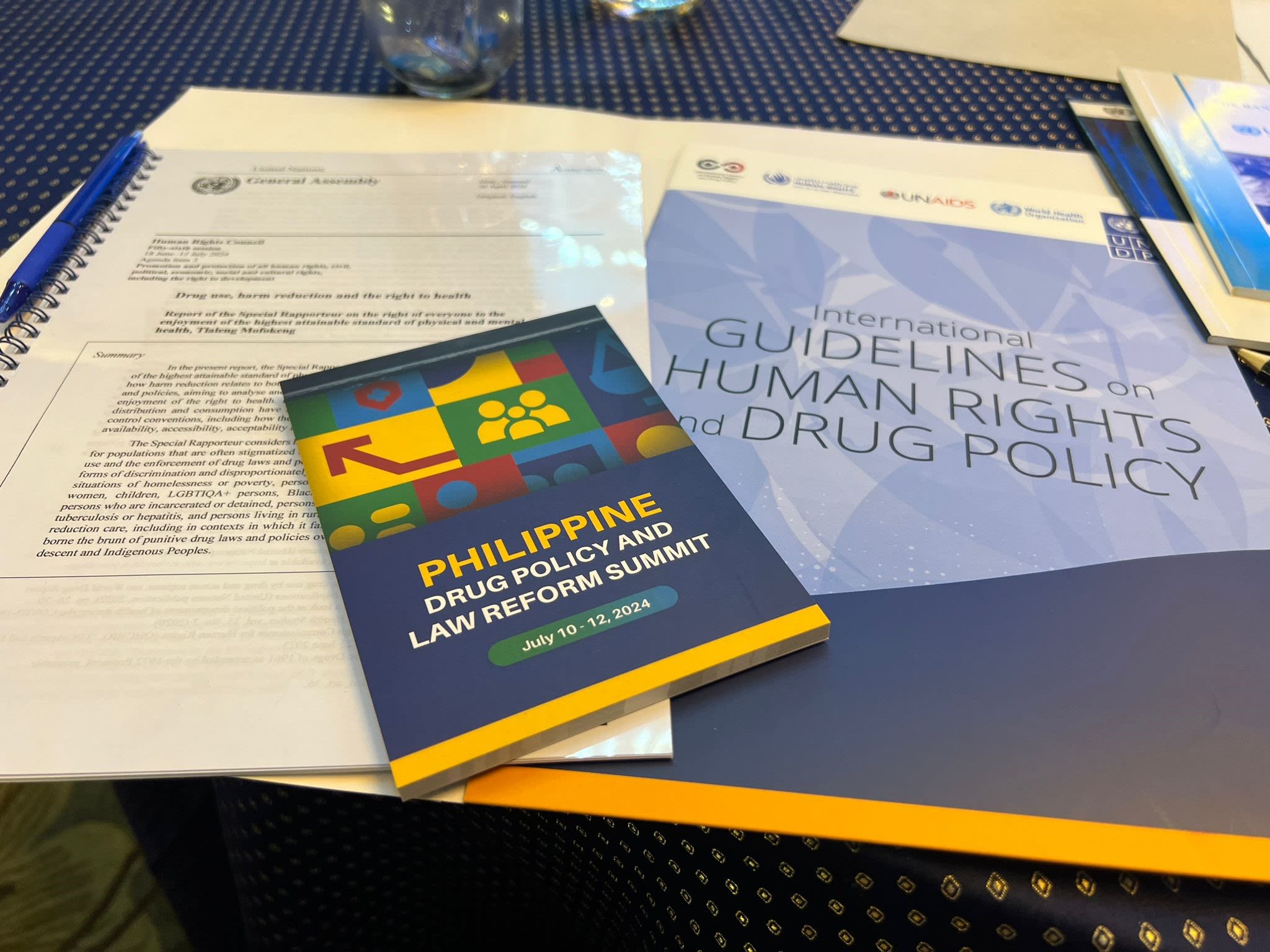

The International Guidelines on Human Rights and Drug Policy were the result of a multi-year collaborative effort between academics, UN entities, civil society addressing Health, governments, and affected communities.

Containing 27 principles, capture the entire human impact of drug control from cultivation to consumption, the Guidelines provide a framework to align national drug laws, policies, and practices with international human rights law.

The Guidelines are not a ‘toolkit’ for a model drug policy, but allow different states and governments to use them as a basis for their own laws, allowing for different interpretations and uses depending on the contexts.

Since their launch in 2019, the Guidelines have supported national reform efforts worldwide, helping to reduce incarceration, promoted access to community support, catalysed dialogue among diverse actors to build a new narrative of rights-based change.

The Guidelines were developed and led by the International Centre on Human Rights and Drug Policy, based at the University of Essex, and the United Nations Development Programme and co-sponsored by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UNAIDS, and the World Health Organisation.

Julie said: “While we recognized from the outset that these Guidelines would provide a critical bridge between international drug control and human rights law, none of us could have anticipated the scale of their influence.

"Their rapid acceptance and proliferation is evidence of their importance."

The project emerged in 2016 when countries around the world called for more attention to human rights in drug policy during a historic General Assembly summit on drugs.

Just seven years later, the Guidelines were recognised in a landmark United Nations Human Rights Council resolution on addressing the world drug situation.

"Surrounded by some of the best minds in the field here at the Human Rights Centre, my collaborators and I were able draw from the Centre's rich legacy of building international human rights soft law standards—putting us in the perfect position to craft these Guidelines with the insights from my colleagues," Julie added.

Leading change around the world

The International Guidelines on Human Rights and Drug Policy are transforming global approaches to drug policy by proving their relevance across Global North and Global South contexts, serving as a catalyst for dialogue and multi-stakeholder engagement, and driving concrete human rights advancements.

Here are just a few examples of how the guidelines are making an impact around the world:

The Mexican NGO, Documenta, and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights have integrated the Guidelines into training sessions to strengthen the capacity of human rights monitoring bodies, helping to address rights violations in compulsory drug detention centers.

Additionally, Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission has incorporated the Guidelines into its monitoring and assessment of residential drug treatment centers to evaluate their compliance with human rights standards.

Building on this momentum, Ms. Hannah has secured funding for a new collaboration with El Centro de Estudios y Acción por la Justicia (CEA-Social Justice), a Mexican grassroots human rights and feminist organization.

Together, they will use the Guidelines to co-design two state-level amnesty laws with local governments, aiming to free women incarcerated for non-violent drug-related offenses.

The Federal Government of Brazil launched the Guidelines in Brasilia in December 2023, catalysing a range of policy actions across the government. The Guidelines are now shaping Brazil’s national drug policy, helping to define the country’s decriminalization model, supporting public defenders, and serving as the framework for its national action plan on drugs.

As part of this new approach, a network of harm reduction centers called Access to Rights and Social Insertion (CAIS) will be established to provide access to rights, social inclusion, and public services for homeless and highly vulnerable individuals affected by drug use. Central to this reform is the plan to decriminalize cannabis use, as recommended in a recent Supreme Court decision.

Another key policy focus is addressing chronic homelessness through a Housing First Pilot, which will embed human rights protections and outcomes into its design, evaluation, and monitoring.

Julie has been invited to join a task team with the Ministry of Justice and collaborators at the University of São Paulo to advise on integrating the Guidelines into these key pillars of Brazil’s national drug policy reform

"The Guidelines are now recognised as the essential tool to strengthen rights-based reform processes across a diversity of global contexts."

The Guidelines have been used to train criminal justice officers, conduct capacity-building activities for people who use drugs, and advocate for criminal justice reform in Nigeria.

The Scottish government has used the Guidelines as a basis for a Charter of Rights for People Affected by Substance Use.

The Charter has been hailed as the first of its kind by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

As part of the process of reform is the goal of reversing the worst record of drug-related deaths in Europe, Scotland has also opened the UK's first safe consumption room in December 2024.

The Guidelines have helped in framing the initial evidence-gathering sessions to understand from those people with life experience of substance use the current barriers and changes needed to realise their rights."

The Guidelines were used to develop a new training package alongside the Ministry of Justice and judges in Albania.

The training was requested for newly appointed criminal court judges, encouraging them to apply human rights when handling drug-related cases.

Albanian courts now actively reference the Guidelines in criminal cases and are supporting alternatives to incarceration for a range of low-level, drug-related charges, including cannabis cultivation.

The Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines convened the first national dialogue on the Guidelines, which laid the foundations for the historic UN Joint Programme on Human Rights in the Philippines to engage constructively on drug policy with the government.

The task team adopted the Guidelines as their operational framework and its final recommendations are helping to reframe national conversations and the country’s national drug policy.

One that more humanely balances a security agenda with public health, development and social protection.

Colombia’s focus on reintegration

Colombia is perhaps one country that has been most devastated by drug prohibition over the last decades.

The Colombian government is now using the Guidelines developed by Julie and her collaborators as a reference point to tackle the problem head-on and end the harms of the war on drugs.

The judiciary in Colombia was one of the earliest adopters of the Guidelines, citing them extensively in historic Constitutional Court judgements on ending the aerial fumigation of coca crops with glyphosate and regulating public consumption of psychoactive substances.

The Guidelines have also helped shape the government’s new national drug policy, which explicitly centres human rights and the Guidelines as its framework for implementation.

One key focus of the national policy is ending the incarceration of woman charged with low-level drug offences through the application of a new Public Utility Law.

This pioneering law, adopts a human rights approach outlined by the Guidelines and allows for a greater understanding of personal circumstances of women involved in the illicit drug markets, for example women living in poverty, as sole heads of households, or unable to work.

Julie and her collaborators in Colombia have convened a series of judicial exchanges to help strengthen judges ability to liberate women from prison and assign them to public service as envisioned by the law.

This is leading to fewer women being given prison sentences, and instead ordered to undertake public service as an alternative to incarceration.

Research into this new approach is now underway in partnership with Dejusticia, a prominent, Colombian human rights organisation and Mujeres Libres, a grassroots NGO in Colombia of formerly incarcerated women.

The teams will interview women who have undergone social re-insertion to see what barriers and problems they are facing reintegrating with society.

The findings will support the Ministry of Justice in designing social interventions.

They will also support the national public defender’s office in engaging in strategic action to ensure every women has an equal chance to benefit from the law.

Julie and her team are testing a dialogical assessment tool which will make it easier for the Guidelines to be used and interpreted at municipality level.

The pioneering tool will be piloted in two Colombian city’s this year.

Public health reform in Ghana

Ghana has positioned itself as a global leader in drug reform and hosted international dialogues around the Guidelines and organising high-level events at the United Nations.

The International Guidelines on Human Rights and Drug Policy has been a critical part of the history of Ghana’s law and policy reforms.

This new approach has seen Ghana change its national drug law, which was reformed to treat drug use and dependence as a health matter, rather than criminal.

In light of these changes, the Government of Ghana formally requested support to convene an interministerial national dialogue on the Guidelines to help build a strategic plan for taking these new changes forward.

This was the first African country to organise such a national dialogue.

Through this process, key gaps and opportunities were identified to strengthen the protection of rights of people affected by drug use in the country.

A further dialogue was convened for Ghanaians to come together as a country and engage actively about the human rights implications of punitive and discriminatory approaches to drugs.

A national roadmap was developed from these discussions, which included the need to implement harm reduction.

This has led to the creation of harm reduction centres set up in 14 districts around the country, supported by six drop-in centres.

The centres act as a place to mitigate the harms of drugs use and provide support to people where possible.

More than 5,000 people who use drugs have been reached by the centres since they were launched following the national dialogue.

A revolution in Pakistan

In 2025, Julie visited Pakistan to aid the government’s historic reform of its drug policy, a move which could herald widespread changes throughout the country to protect human rights.

Julie met with government ministers, civil servants, judges, and ambassadors to discuss how putting human rights at the forefront of the country’s drug policies is key to reform.

Ms Hannah also spent a day with municipal and district court judges at the Federal Judicial Academy to discuss how the Guidelines can be implemented on a practical level.

Judges were also introduced to a new online course developed in collaboration with the Academy and the Justice Project Pakistan, explaining the Guidelines and the role of the judiciary in its effective implementation.

Ms Hannah said: “Pakistan is not alone in seeking reform to its drug policies.

"It is hard and courageous work but there is a lot of inspiration to draw on around the world where other countries have made changes for the better.

“This is a truly historic moment for Pakistan and will increase the momentum behind the human rights movement in the country.

"Pakistan’s story could also play a catalytic role in advancing reforms throughout the South and East Asia region.”

Following Ms Hannah’s visit, a judge in Pakistan used the International Guidelines on Human Rights and Drug Policy to support their judgement in a case which saw a vulnerable mother, languishing in pre-trial detention for a drug offence, freed from prison.

“We welcome the technical support and experience sharing of the Guidelines as we map out a reform pathway for Pakistan’s counter-narcotics law,” said Barrister Aqeel Malik, Government Spokesperson for Legal Affairs at the Ministry of Justice and Law in Pakistan.

"To see international human rights law explicitly integrated into the day-to-day decision-making of judges is unprecedented."

Find out more

Human Rights Centre

40 years pioneering the theory and practice of human rights from the local to the global.

Study Human Rights at Essex

Studying human rights develops the skills and confidence to advocate for individual and community rights, social justice and social change.

Sixty Stories

We’re celebrating 60 years of making change happen. 60 years of boldness and bravery from our students past and present. 60 years of creating change.